Last week I noticed this small article posted twice to Facebook by two different renowned Quebec antique dealers Michel Prince and Karin Belzile. It is a short history of the Bourgault family who started the well known wood carving community of Saint-John-Port-Joli. Even if you know little of Quebec carving, you have probably run across a carving or lamp created by one of these traditional artists. Perhaps at the cottage of a friend. Many people who have visited the community over the years have picked up a memento, and many of these are destined for the rustic summer home.

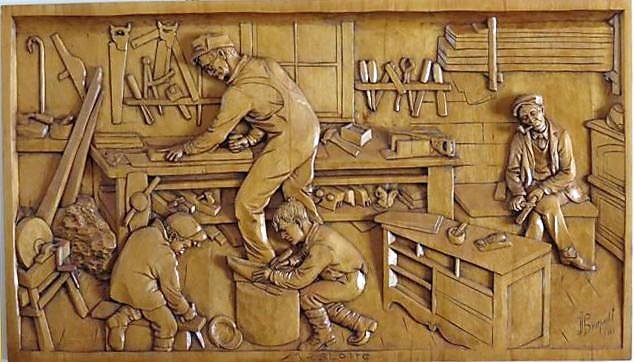

For years I didn’t really gravitate to this work, finding it more craft than art, but I eventually began to see some pieces that I really admired. Mostly family or village scenes from Medard, who would on occasion paint the carvings in fine detail. I recall a scene of a Sunday dinner, complete with turkey, and a completely set table. The family looking on as father was about to set to work carving. Both the expressions of the people, and over-all integrity of the depiction made it live for me. Since then I have considered the work more closely.

So here is the article, translated to the best of my ability, which serves as a “starter” to the famous Bourgault family, and the carving town of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli. If you google their, or the town’s name you will come up with lots of stuff. Or better still, swing by there and see for yourself.

The importance of the Bourgault Family in the world of sculpture in Quebec.

Since the 1930s, the Bourgault family of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli has been world renown for wood crafts.

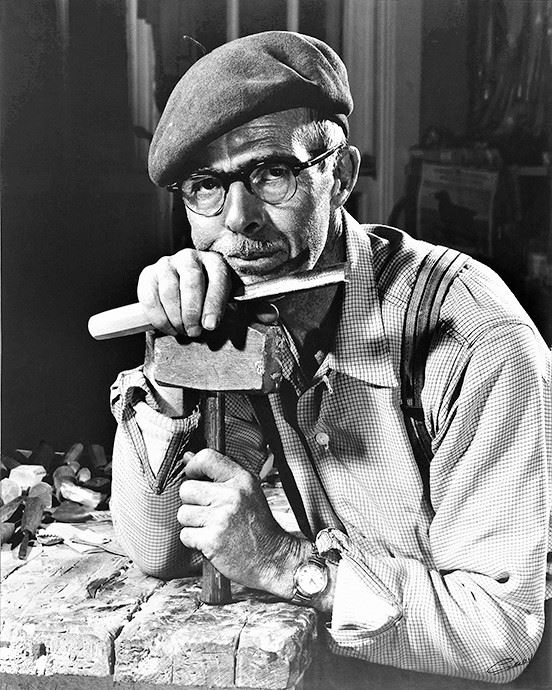

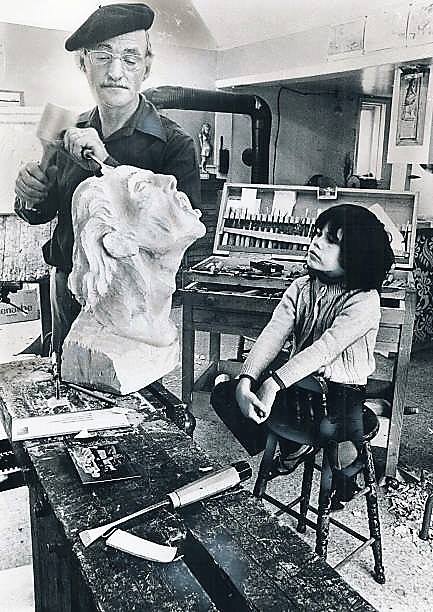

The son of a carpenter from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Médard Bourgault (1897-1967) began working with wood at a very young age using a simple pocket knife. Like many other young men in his parish, he worked on ships, and his interest in sculpture increased with the leisure hours spent at sea. In 1918, he began to manufacture furniture and sculptures in the paternal workshop. The following year, he transformed an old shed into a workshop and often visited Arthur Fournier, a woodworker, who would guide him. During the 1920s, Medard made mostly furniture, but he also made crucifixes and other religious objects. He earns his living working alongside his father.

Starting in 1929, Medard’s sculptures became increasingly popular among collectors, who discovered them through the ethnologist Marius Barbeau and the man of letters and politician Georges Bouchard. They are the ones who encourage Médard to revive the local scenes. In the midst of the economic crisis, Medard, for whom carpentry work was rare, opened a craft counter on the side of the road. In 1931, he invited his brothers Jean-Julien (1910-1996) and André (1898-1957) to work with him, and he began to participate in exhibitions in Quebec and Toronto. The Government of Quebec began to buy from the brothers. Without planning it, the Bourgault brothers had revived Quebec crafts.

From 1933 on, the three brothers specialized. Medard devoted himself above all to religious sculpture. He made statues for religious communities and carved the ornamental woodwork in many churches. Jean-Julien and André continue for their part to portray the rural peasant culture. Soon their sister Yvonne also joins the company, as well as nephews and other young people from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli.

In 1940, the Quebec government transformed the Bourgault brothers’ workshop into a sculpture school, whose management was entrusted to Médard. André became the director in 1952 and Jean-Julien in 1958. From 1964 to 1986, it was the turn of Jean-Pierre, son of Jean-Julien, to assume the direction.

Saint-Jean-Port-Joli now bears the name of “capital of sculpture” in Quebec. With the years and the increasing number of local sculptors, the art has diversified and is renewed, as evidenced by the creation of works in resin, stone, granite, clay and bronze. Other forms have been added, including painting.

Source, https://sites.ustboniface.ca/francoidenti…/…/texte/T3086.htm

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

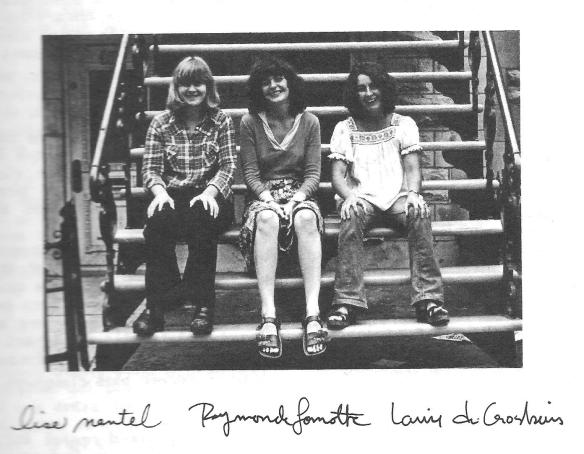

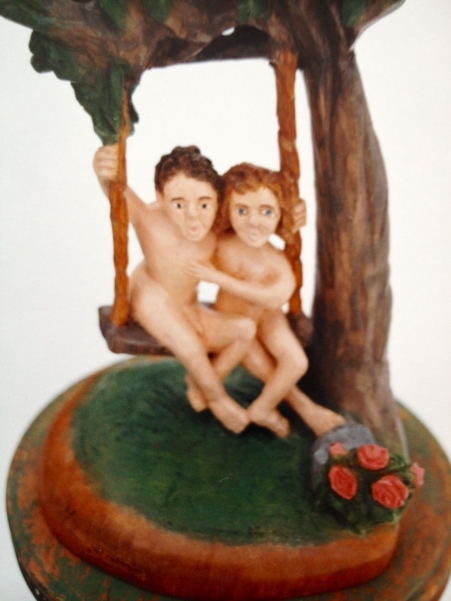

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

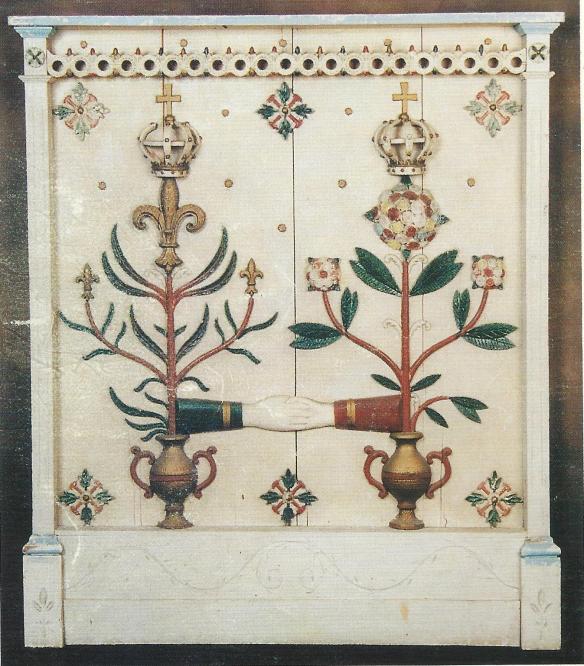

In the mid 1990’s we did what turned out to be a one time show in the Laurentians ski area north of Montreal. During ski season in the club house of a popular ski hill. The assumption was that the multitude of skiers would come off the slopes and couldn’t help themselves from wandering through the show and selecting a few prime antiques for their ski chalets. Turns out this assumption was wrong, and we spent three days watching people ski, and then going directly to their cars and leaving. We rented a chalet with friends and so when we were not busy doing nothing at the show we at least had some good food and laughs in commiseration. It turned out to be a pretty expensive venture which didn’t really pay off, if it was not for the fact that in being there we came across one of the best and most important pieces of Quebec folk art we had ever encountered.

In the mid 1990’s we did what turned out to be a one time show in the Laurentians ski area north of Montreal. During ski season in the club house of a popular ski hill. The assumption was that the multitude of skiers would come off the slopes and couldn’t help themselves from wandering through the show and selecting a few prime antiques for their ski chalets. Turns out this assumption was wrong, and we spent three days watching people ski, and then going directly to their cars and leaving. We rented a chalet with friends and so when we were not busy doing nothing at the show we at least had some good food and laughs in commiseration. It turned out to be a pretty expensive venture which didn’t really pay off, if it was not for the fact that in being there we came across one of the best and most important pieces of Quebec folk art we had ever encountered. “Maple Sugar Time”

“Maple Sugar Time”