The following article was originally printed in “Antiques and Art” magazine, July / August 1977 issue. It was written by Nora Sterling and Jackie Kalman. This article serves as a useful introduction to folk art, and it is also interesting to note how much folk art has grown in recognition and popularity over the past thirty years.

The following article was originally printed in “Antiques and Art” magazine, July / August 1977 issue. It was written by Nora Sterling and Jackie Kalman. This article serves as a useful introduction to folk art, and it is also interesting to note how much folk art has grown in recognition and popularity over the past thirty years.

CANADIAN FOLK ART

By NORA STERLING and JACKIE KALMAN

|

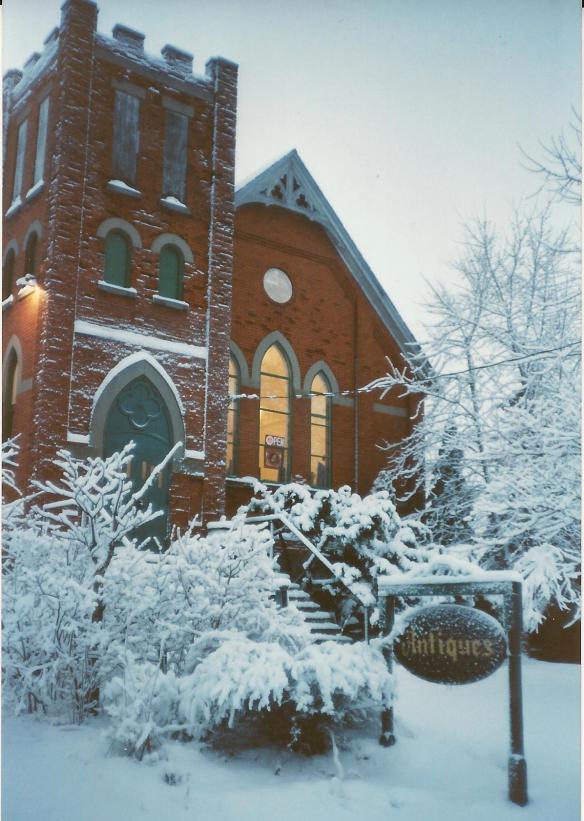

When the Bowmanville Antiques and Folk Art Show opened its doors this year, waiting with the throng to enter were two people very significant by their presence. They were buyers from the Museum of Man and the National Gallery in Ottawa. The academically oriented National Gallery soon will be opening its folk art room and, in anticipation, has been collecting for the past few years. By buying and displaying folk art, these prestigious institutions announce to Canadians what other more culturally secure countries have acknowledged for at least 50 years: folk art has finally come of age. In the United States, as early as the 1920s, families like the Rockefellers, DuPonts and Whitneys had major collections of folk art, much of which now reside in three New York museums: the Metropolitan, the Whitney and the Museum of Modern Art. In Canada, folk art is just being recognised as a viable and valid art form with qualities of freshness, inventiveness and vigour that make it exciting. What gives folk art its originality and charm is that, fortunately, the gifted artists who produced it are free from the dogmas and restrictions which the academic world imposes. Folk art is not merely a quaint reminder of a nation’s manners and mores, a thing of the past with only functional or merely decorative purposes. It may indeed have all of these attributes, but like all good art, its expressions are powerful and compelling with an originality of concept, creativity of design, craftsmanly use of the medium and flashes of inspiration that are not surpassed by many academic artists. Keeping in mind the similarities between academic and folk artists, the distinctive difference is that the latter is unschooled, while not necessarily unskilled. For example, a folk artist may have been whittling from his youth, creating bits and pieces for his own pleasure in his spare time. As an adult he may have become a white collar worker or perhaps a farmer, while still retaining his interest and further developing his skill. |

|---|

Donald Hays is such a folk artist. Carving since he was five years old, he is .now in his early 40s and an engineer by profession. He carves bird decoys which he paints with the incredible expertise and attention to detail of an Audubon. With the true artist’s eye, he chooses those idiosyncratic stances and important characteristics that are peculiar to the bird he is carving.

Donald Hays is such a folk artist. Carving since he was five years old, he is .now in his early 40s and an engineer by profession. He carves bird decoys which he paints with the incredible expertise and attention to detail of an Audubon. With the true artist’s eye, he chooses those idiosyncratic stances and important characteristics that are peculiar to the bird he is carving.

On the other hand, Collins Eisenhauer, a folk artist who, like Grandma Moses, has “made it,” did not start intensive wood carving until 1964, when he was 66 years old. When asked what he did for a living in the ’30s, Eisenhauer replied, ” I wouldn’t like to tell you! ” He does admit, however, to being a farm hand, a logger and a sailor. His work has been bought by the Museum of Man, the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia and the National Gallery in Ottawa.

Though carved from big hunks of wood, his figures still have a two dimensional look about them. They have the static and stiff quality which is characteristic of naive art – as if the artist does not want to risk a trial of skill to depict movement.

Charles Tanner, an ex-fisherman from Nova Scotia, approaches the task of carving with even a lesser degree of academic knowledge of the craft of sculpture than Eisenhauer. He solves his technical problems simply, by a complete disregard of detail and a disrespect for proportion which, in effect, enhance his work. One is struck by his bold personal style – exuberant, colourful and direct. His sculptures are now on tour with an exhibit of Canadian art assembled by the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia.

At this juncture, decoys became folk sculpture. The link with the folk genre lies in the carver’s craftsmanship and especially in his personal interpretation of the salient characteristics of his quarry.

Sculpture is only one way in which the power and beauty of folk art is expressed. Rugs, quilts, paintings, furniture and accessories are among the wide variety of objects produced by folk artists.

Sculpture is only one way in which the power and beauty of folk art is expressed. Rugs, quilts, paintings, furniture and accessories are among the wide variety of objects produced by folk artists.

Much has been written on folk art, albeit not Canadian. Many art historians, curators and artists have concluded that the expressions of folk art are world-wide and that they state universal truths – realities which will always be voiced by untrained people with a creative urge.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Barber, Joel. Wild Fowl Decoys. New York: Windward House, 1934. Reprinted New York: Dover Public- ations, 1954.

Bishop, Robert. American Folk Sculpture. New- York: E.P. Dutton and Company, 1974.

Folk Sculpture U.S.A. Edited.by Herbert W. Hemphill Jr. The Brooklyn Museum and the Los kngeles County Museum of Art. Catalogue- for 1976 show.

Folk Art of Nova Scotia. Art gallery of Nova Scotia, Halifax, Nova Scotia. Catalogue for show, November 1976 through May 1978. Biographies of artists and illustrations of their works.

Gladstone, M.J. A Carrot for a Nose:, the Form of Folk Sculpture on America’s City Streets and Country Roads. New York: Charles Scribner’s Song, 1974.

Hooked Rugs in the Folk Art Tradition. Museum of American Folk Art, New York. Catalogue for 1974 show.

Lipman, Jean and Winchester, Alice.The Flowering of American Folk Art, 1776-1876. New York: The Viking Press in cooperation with the Whitney Museum of American Art, 1974.

People’s Art: Naive Art in Canada. J. Russell Harper. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa. Catalogue for, show, 1973-1974.

The April Antiques and Folk Art Show. Mel Shakespeare. Catalogue for the 1975 Bowmanville, Ontario, show.