It’s 4:30 pm April 20, 2018, and I am declaring it spring. I just had to run out to my friends place on the edge of town to deliver a painting I had cleaned for them, and when I got out of the car, I thought, “Hallelujah. at last, it’s spring. What a long wait it has been for us here in south-west Ontario this year. But it’s like being beaten over the head with a two by four, it feels so good once it’s over. I point this out to say it took a lot of will power to reject the offer of a beer and sitting on the porch for a spell for me to write this, but I met a guy at the market last week who pointed out he noticed I was getting a bit irregular in writing every Friday as I was until recently, and he gently encouraged me to get with it. It doesn’t take much to make me feel guilty apparently. But what does this have to do with economics you ask. Well nothing, but the arrival of spring could not go without comment.

What got me to thinking about economics this week is a new pair of blue jeans I bought at Costco. I buy clothes only when necessary which at my age is rarely. I’ve got a lot of clothes and not many occasions when I need to dress up, plus I am not much of a shopper. Anyway, seventeen bucks. I got a really nicely made jeans of quality fabric that fit me and look good for less than the price of a coffee and a snack at Starbucks. I also had the occasion that day to be in the Bay and I saw some designer jeans for about $240. I didn’t like the fancy stitching on the back pockets but I suppose it was there so people knew you hadn’t bought your jeans at Costco for seventeen bucks, and that’s fine with me. I’m not going to diss anybody for wanting to make a statement with their clothes, if that’s what makes you feel better. It just doesn’t do anything for me. I also know that if I looked around I could probably find a pair of jeans for $5, but if you want them to last you’re better off to spend a little more. My point is you can spend $15 or you can spend $245, or more for a pair of men’s jeans. You can pay anything for anything these days

Next example. We were at our daughter’s house and over breakfast she said to her husband “when you go out to get the groceries I would like you to go to a hardware store and get a new drip coffee maker.” This was the direct result of having to listen to me once more mutter under my breath when I tried to pour myself a cup of coffee and inevitably, no matter how hard you tried, the stupid spout of the carafe was so tiny that you ended up spilling all over the counter. That, and the fact that it no longer had a lid and she doesn’t like the smell of coffee. I find this hard to relate to because I love the smell of coffee, but I did agree with her that the spilling thing was a pain in the ass. Of course it is not in my nature to replace anything that still works so I objected. I would have put up with that stupid carafe until the thing died a natural death. Also, the fact is that neither of them drink coffee so the coffee maker is just there for us or other coffee drinking guests so is rarely used. But she showed great determination so I headed out with my son in law, figuring that I would jump in at the last minute and buy the device as a hostess gift. As it turns out he wouldn’t let me do this but I digress. We went first to the local Loblaws for the groceries on our list, and low and behold, there in the middle isle was a very nice little coffee maker on sale for $22. Amazing. It has a spout that pours, a lid, a cleanable filter so you don’t have to buy and dispose the paper filters, and I can tell it makes a much better cup of coffee than the old one. I think I may have learned something from the experience. Spending $22 to not have to wipe up spilled coffee is a good move. When I got home and looked at the Canadian Tire catalogue I noticed you can spend anywhere from $12 to about $350 for a drip coffee maker. You can pay anything, for anything these days.

This seems to be the case for most items these days thanks to diverse world economics, and the modernization of manufacturing, and I think it’s a pretty good thing overall. The frugal or poor can buy pretty good things for not much money, and the wealthy have an ever increasing selection to choose from. However, I think it also makes people suspicious of their understanding of the monetary value of things.

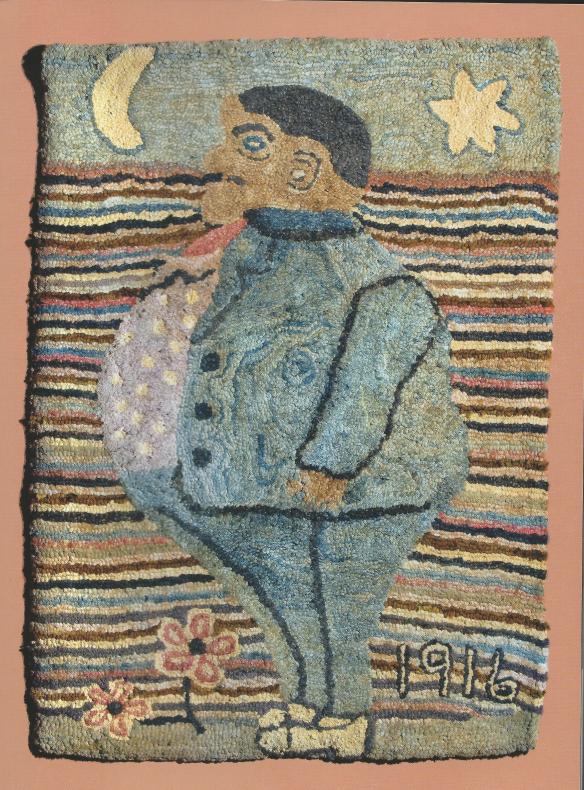

This has always been an issue that antique and art dealers have had to deal with. When you are asking $350 for a 100 year old rocking chair, there is no price in a catalogue to refer to. There is just your knowledge of antiquity and markets which the buyer either believes in or not. I believe that a lot of established, knowledgeable dealers do a good and fair job of pricing, but it is also the case with the way the markets are now that you see prices all over the place. Recently, a painting by a folk artist that I represented for years sold at auction for $870. I sold that painting in my shop for $495, and I know of other auctions were similar paintings by the same artist have sold for less than $100.

I once overheard a couple of old time dealers haggling over the price of a chair. “Well I agree that it is a very nice chair in original paint and great condition but why is it priced at $600.” The other guy looked him strait in the face and said “because I paid $5 for it”. Ha. They both laughed, and the questioning fellow knew that his negotiation technique was failing but you get the point. You can pay anything, for anything these days. He may have only had to pay $5 but his knowledge of antiques made him realize it was worth much more. I think this is the basic appeal behind the business. It’s a treasure hunt. That, and a love for the stuff. You need that too, or you will never be able to make a go of it.

And don’t get me started on how this affects you when you are trying to do a decent job of appraising items for fair market value. That’s a topic for another day. I’ve gone on long enough. It’s sunny on the porch and I am dying to go out there and have a beer. I’m not a big beer drinker mind you. Don’t touch the stuff all winter, and really don’t drink much in the summer, but on the first day of spring, who would deny me? Happy spring everyone.