Last week I noticed this small article posted twice to Facebook by two different renowned Quebec antique dealers Michel Prince and Karin Belzile. It is a short history of the Bourgault family who started the well known wood carving community of Saint-John-Port-Joli. Even if you know little of Quebec carving, you have probably run across a carving or lamp created by one of these traditional artists. Perhaps at the cottage of a friend. Many people who have visited the community over the years have picked up a memento, and many of these are destined for the rustic summer home.

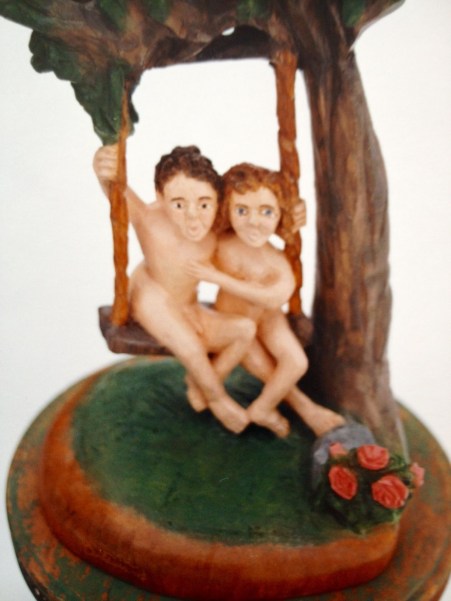

For years I didn’t really gravitate to this work, finding it more craft than art, but I eventually began to see some pieces that I really admired. Mostly family or village scenes from Medard, who would on occasion paint the carvings in fine detail. I recall a scene of a Sunday dinner, complete with turkey, and a completely set table. The family looking on as father was about to set to work carving. Both the expressions of the people, and over-all integrity of the depiction made it live for me. Since then I have considered the work more closely.

So here is the article, translated to the best of my ability, which serves as a “starter” to the famous Bourgault family, and the carving town of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli. If you google their, or the town’s name you will come up with lots of stuff. Or better still, swing by there and see for yourself.

The importance of the Bourgault Family in the world of sculpture in Quebec.

Since the 1930s, the Bourgault family of Saint-Jean-Port-Joli has been world renown for wood crafts.

The son of a carpenter from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli, Médard Bourgault (1897-1967) began working with wood at a very young age using a simple pocket knife. Like many other young men in his parish, he worked on ships, and his interest in sculpture increased with the leisure hours spent at sea. In 1918, he began to manufacture furniture and sculptures in the paternal workshop. The following year, he transformed an old shed into a workshop and often visited Arthur Fournier, a woodworker, who would guide him. During the 1920s, Medard made mostly furniture, but he also made crucifixes and other religious objects. He earns his living working alongside his father.

Starting in 1929, Medard’s sculptures became increasingly popular among collectors, who discovered them through the ethnologist Marius Barbeau and the man of letters and politician Georges Bouchard. They are the ones who encourage Médard to revive the local scenes. In the midst of the economic crisis, Medard, for whom carpentry work was rare, opened a craft counter on the side of the road. In 1931, he invited his brothers Jean-Julien (1910-1996) and André (1898-1957) to work with him, and he began to participate in exhibitions in Quebec and Toronto. The Government of Quebec began to buy from the brothers. Without planning it, the Bourgault brothers had revived Quebec crafts.

From 1933 on, the three brothers specialized. Medard devoted himself above all to religious sculpture. He made statues for religious communities and carved the ornamental woodwork in many churches. Jean-Julien and André continue for their part to portray the rural peasant culture. Soon their sister Yvonne also joins the company, as well as nephews and other young people from Saint-Jean-Port-Joli.

In 1940, the Quebec government transformed the Bourgault brothers’ workshop into a sculpture school, whose management was entrusted to Médard. André became the director in 1952 and Jean-Julien in 1958. From 1964 to 1986, it was the turn of Jean-Pierre, son of Jean-Julien, to assume the direction.

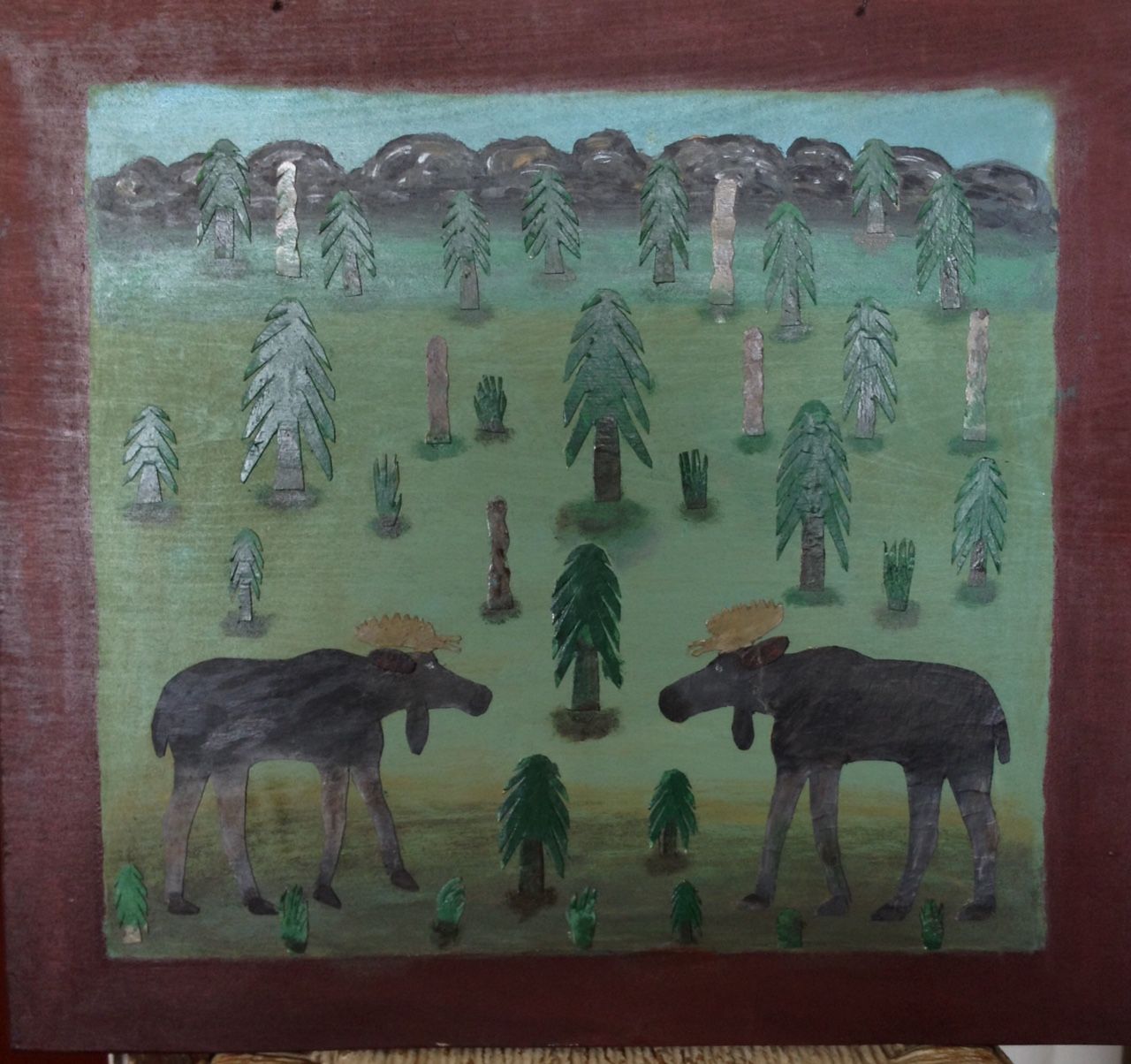

Saint-Jean-Port-Joli now bears the name of “capital of sculpture” in Quebec. With the years and the increasing number of local sculptors, the art has diversified and is renewed, as evidenced by the creation of works in resin, stone, granite, clay and bronze. Other forms have been added, including painting.

Source, https://sites.ustboniface.ca/francoidenti…/…/texte/T3086.htm

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

By the mid-nineties we were doing a lot of business with Quebec collector, Pierre Laplante. He was, at the time a very successful dentist, and determined collector of Quebec antiquity and contemporary folk art. A very good fellow who we enjoyed meeting up with every few weeks at his country home, where typically after a good meal and a little wine was consumed we would inevitably end up in his converted machine shed, which was stuffed to the walls with wonderful things, so that I might buy some of what he was prepared to let go of. At the time he was keeping five or six pickers busy full time in an attempt to find him the “all” of the best pieces available. They would bring in full truck loads and he would usually buy everything to get the best price, and assure their dedication. He would sell me all the stuff he didn’t want to keep at very reasonable prices, and that kept me coming back. His appetite was voracious and he rarely said no so there was a lot of stuff arriving. For a couple of years before we both slowed down we did a lot of great business together.

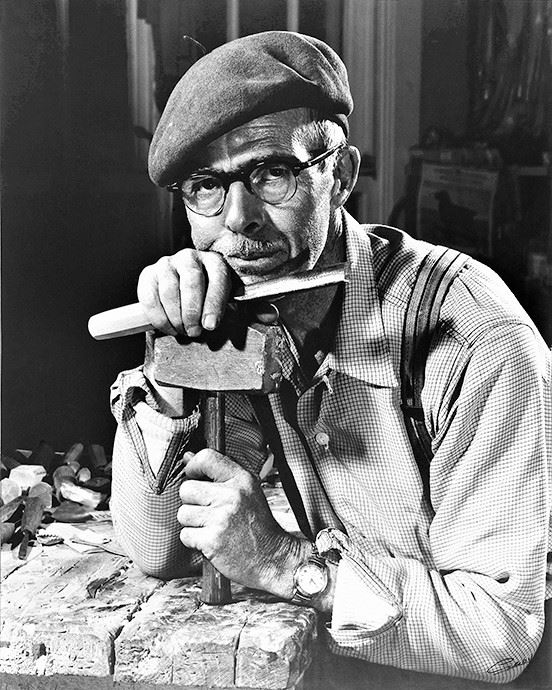

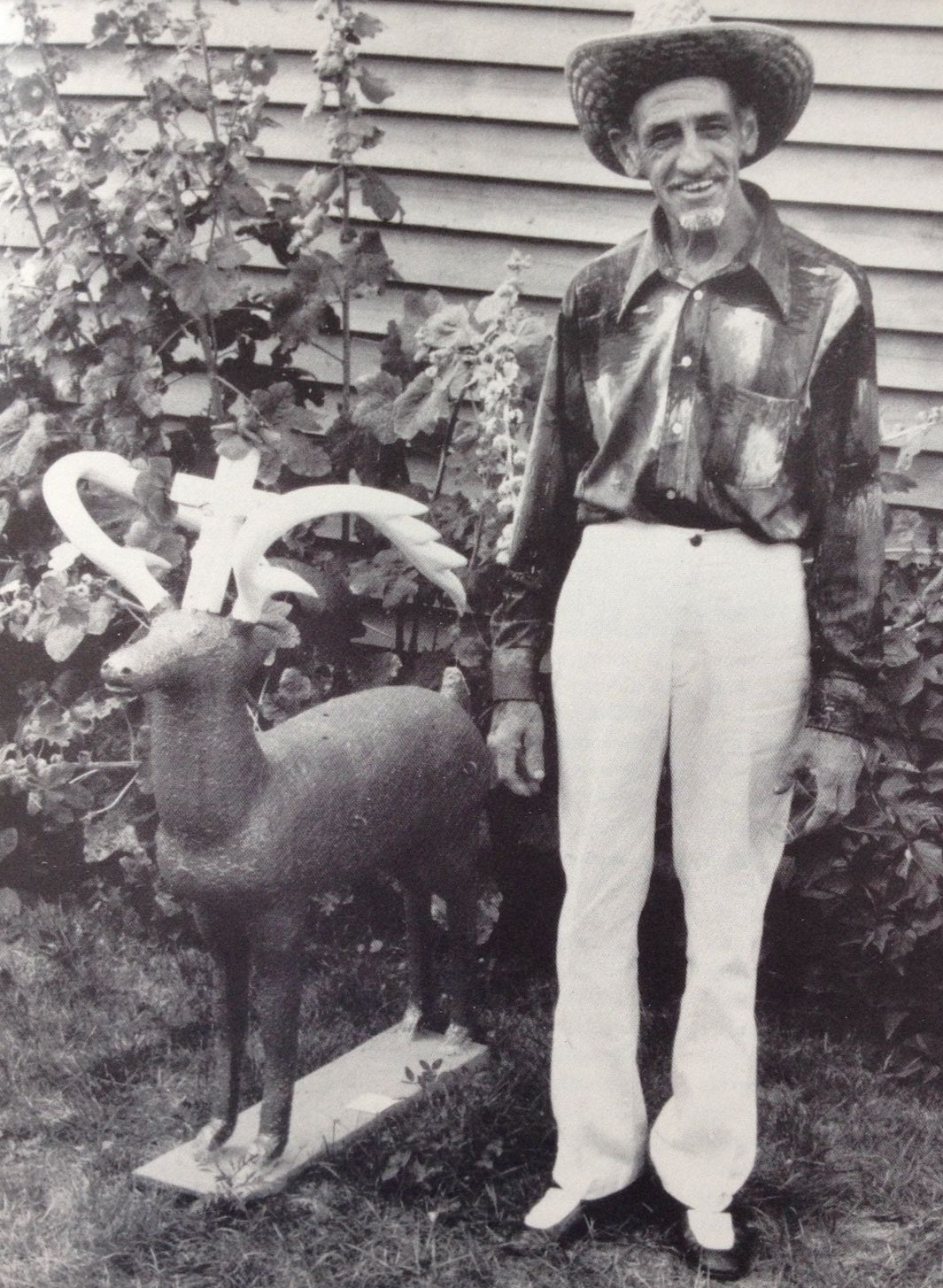

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

Rene Dandurand’s carvings are worked in one piece from a solid butternut or pine block. Some early works are left bare, showing the grain, but most are painted by his wife Julienne, an excellent colourist, after lengthy consideration of suitable colours. Although Dandurand’s children supplied him with a full set of carving chisels, he prefers the familiarity of his two or three ordinary old knives.

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996.

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996. Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

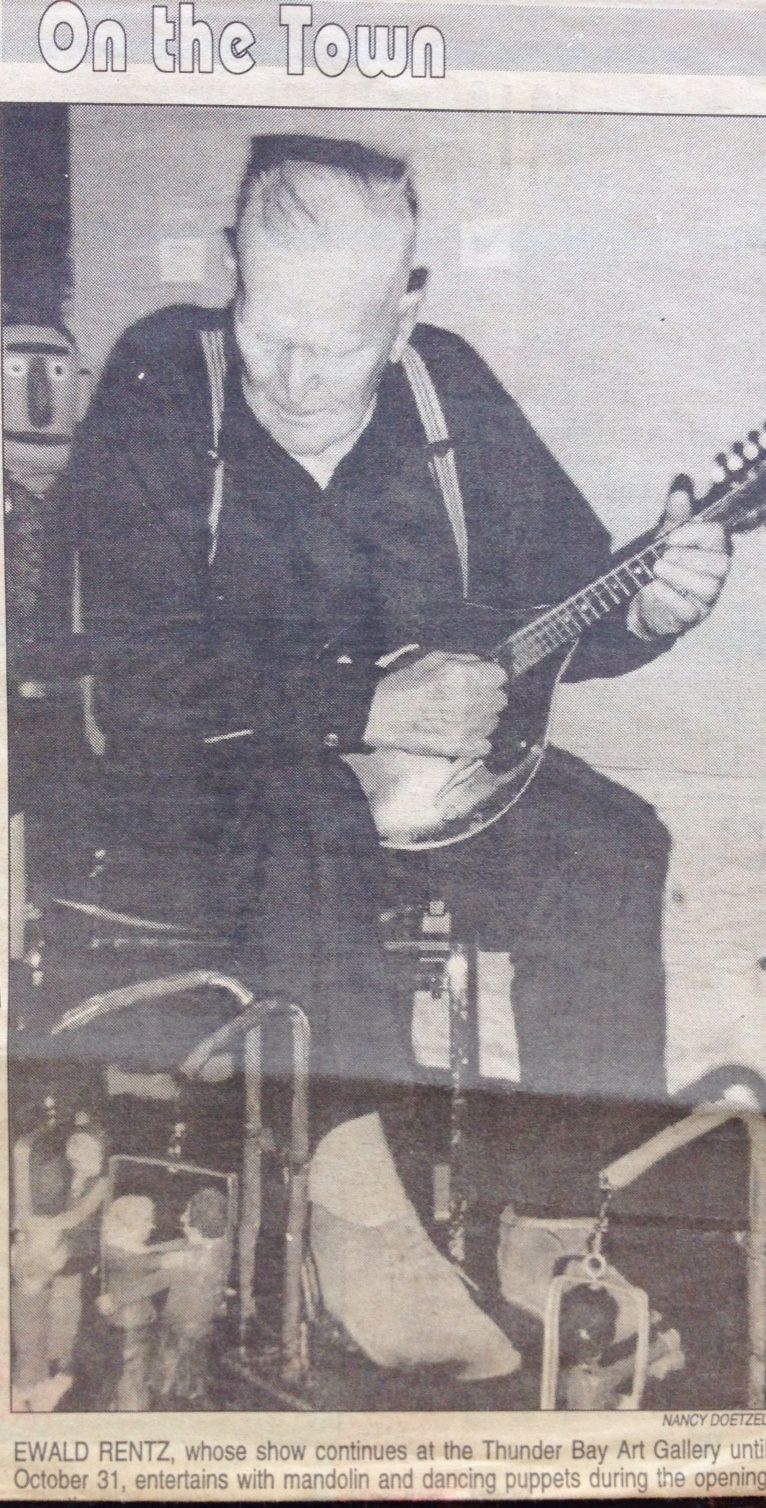

Last week I told the story of recently meeting up with Ewald Rentz’ niece Alyss, and I reproduced an article on the artist from the local paper from 1978. This week I will finish by presenting some more of her observations, and additional photos taken by her of his home and barber shop in Beardmore. I am also going to reproduce an article written by the Thunder Bay Chronicle- Journal on the occasion of his retrospective show at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery in 1993.

Last week I told the story of recently meeting up with Ewald Rentz’ niece Alyss, and I reproduced an article on the artist from the local paper from 1978. This week I will finish by presenting some more of her observations, and additional photos taken by her of his home and barber shop in Beardmore. I am also going to reproduce an article written by the Thunder Bay Chronicle- Journal on the occasion of his retrospective show at the Thunder Bay Art Gallery in 1993.

I love it when good things fall out of the blue, right into your lap. It had been a long time since the cosmos had flipped me a lucky card, and I remember thinking about a month ago that perhaps things were quiet because I had been out of the circle for so long (my last show being Bowmanville in 2014) that collectors had basically forgotten about me. It seemed a reasonable assumption, even after 30 years in the business, because it can be a case of what have you done for me lately. But then two things happened. First, I had a call from a Montreal folk art collector I have known for years, but had not heard from for at least ten. He explained that his wife had died recently and it had come time to downsize and disperse the collection. He has some great things so I am looking forward to starting this process. Then the following day I got a call from a lovely woman from Thunder Bay named Alyss Rentz. She was married to Gary Rentz who was Ewald Rentz’ nephew. I am a huge Rentz fan, and it had been a long time since anyone from the family had contacted me. Alyss explained that her husband had died and she too was downsizing; and she has five pieces by Ewald that she would like to sell. As it happened she was coming to Hamilton the following week to visit relatives and she could bring the pieces with her. She described the pieces and after seeing hundreds of Rentz’s over the years I knew from her description that I was interested. She told me she would call when she arrived in Hamilton. Great! I was immediately looking forward to it.

I love it when good things fall out of the blue, right into your lap. It had been a long time since the cosmos had flipped me a lucky card, and I remember thinking about a month ago that perhaps things were quiet because I had been out of the circle for so long (my last show being Bowmanville in 2014) that collectors had basically forgotten about me. It seemed a reasonable assumption, even after 30 years in the business, because it can be a case of what have you done for me lately. But then two things happened. First, I had a call from a Montreal folk art collector I have known for years, but had not heard from for at least ten. He explained that his wife had died recently and it had come time to downsize and disperse the collection. He has some great things so I am looking forward to starting this process. Then the following day I got a call from a lovely woman from Thunder Bay named Alyss Rentz. She was married to Gary Rentz who was Ewald Rentz’ nephew. I am a huge Rentz fan, and it had been a long time since anyone from the family had contacted me. Alyss explained that her husband had died and she too was downsizing; and she has five pieces by Ewald that she would like to sell. As it happened she was coming to Hamilton the following week to visit relatives and she could bring the pieces with her. She described the pieces and after seeing hundreds of Rentz’s over the years I knew from her description that I was interested. She told me she would call when she arrived in Hamilton. Great! I was immediately looking forward to it.

Gnarled Branches, Knots, made into Objects of Art, by Gerry Poling

Gnarled Branches, Knots, made into Objects of Art, by Gerry Poling

In the mid 1990’s we did what turned out to be a one time show in the Laurentians ski area north of Montreal. During ski season in the club house of a popular ski hill. The assumption was that the multitude of skiers would come off the slopes and couldn’t help themselves from wandering through the show and selecting a few prime antiques for their ski chalets. Turns out this assumption was wrong, and we spent three days watching people ski, and then going directly to their cars and leaving. We rented a chalet with friends and so when we were not busy doing nothing at the show we at least had some good food and laughs in commiseration. It turned out to be a pretty expensive venture which didn’t really pay off, if it was not for the fact that in being there we came across one of the best and most important pieces of Quebec folk art we had ever encountered.

In the mid 1990’s we did what turned out to be a one time show in the Laurentians ski area north of Montreal. During ski season in the club house of a popular ski hill. The assumption was that the multitude of skiers would come off the slopes and couldn’t help themselves from wandering through the show and selecting a few prime antiques for their ski chalets. Turns out this assumption was wrong, and we spent three days watching people ski, and then going directly to their cars and leaving. We rented a chalet with friends and so when we were not busy doing nothing at the show we at least had some good food and laughs in commiseration. It turned out to be a pretty expensive venture which didn’t really pay off, if it was not for the fact that in being there we came across one of the best and most important pieces of Quebec folk art we had ever encountered. “Maple Sugar Time”

“Maple Sugar Time”

Back in the 1990’s I would occasionally get a call from a friend, Marty Ahvenus, who owned and operated the Village Book Store on Queen St at the time. He was a book seller by trade who also enjoyed folk art and making periodic trips to the East Coast. When he returned from a trip he was in the habit of phoning me, and selling me the folk art which he had acquired enroute. We would meet at a French restaurant on Baldwin Street which offered fish soup, a favourite of both of us, and I remember that the owner/chef would always come out to see who had ordered the soup as so few did. But that’s another story.

Back in the 1990’s I would occasionally get a call from a friend, Marty Ahvenus, who owned and operated the Village Book Store on Queen St at the time. He was a book seller by trade who also enjoyed folk art and making periodic trips to the East Coast. When he returned from a trip he was in the habit of phoning me, and selling me the folk art which he had acquired enroute. We would meet at a French restaurant on Baldwin Street which offered fish soup, a favourite of both of us, and I remember that the owner/chef would always come out to see who had ordered the soup as so few did. But that’s another story.