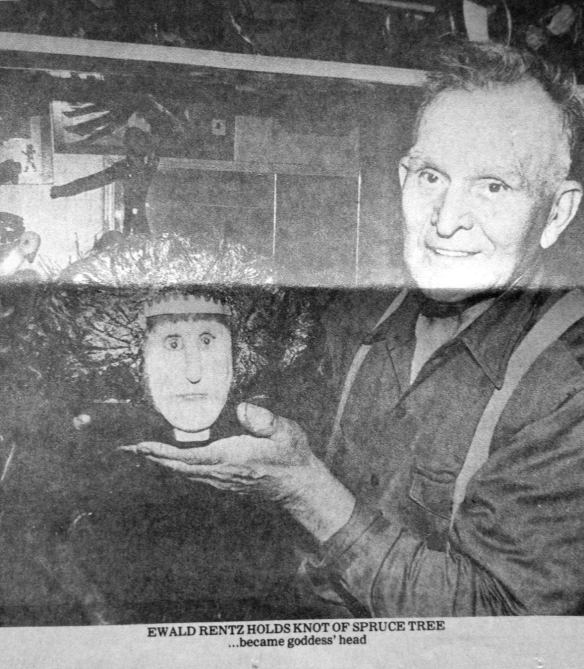

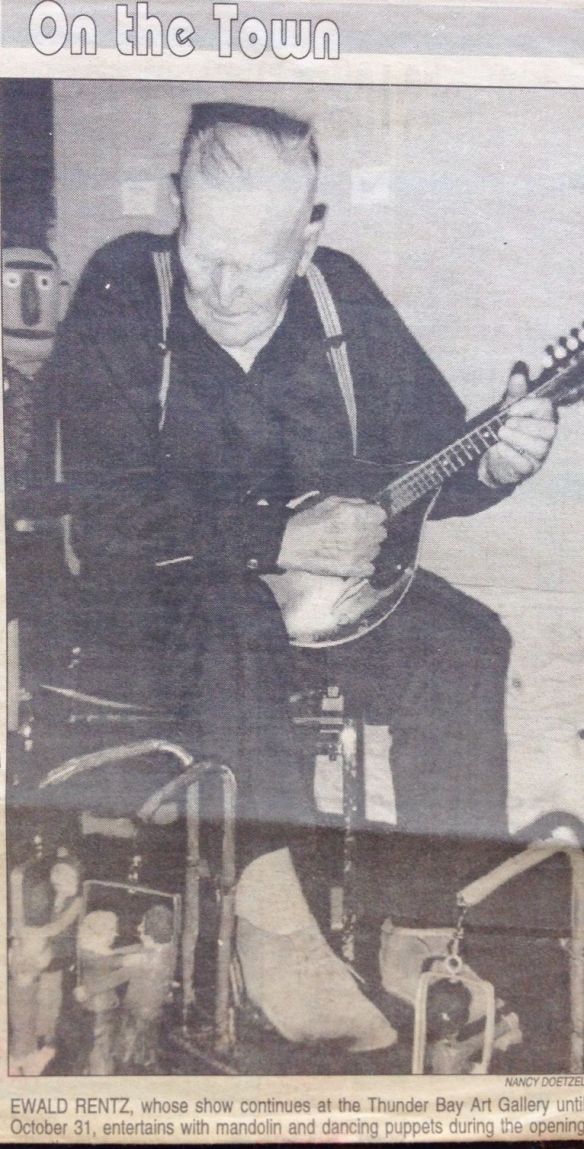

Rentz performing at his opening

I was just going through some papers and found an article about Beardmore, Ontario folk artist Ewald Rentz written by Canadian humourist Arthur Black. We enjoyed listening to his radio programme “Basic Black for many years on the C.B.C., and reading his syndicated weekly humour column. I don’t know how I came by this transcript of a 1994 show he did on Ewald Rentz, but the content is sufficiently interesting that I thought to reproduce it here to add to the (hopefully) permanent record of this significant Canadian folk artist. In looking him up I noticed Arthur Black started his column in 1976 in Thunder Bay, so it makes sense that he would become aware of, and write about a folk artist who lived so nearby. Arthur Black died Feb 21, 2018, from pancreatic cancer at the age of 74. Three time winner of the Stephan Leacock Award for Humour, he will be remembered for his humour, and the large contribution he made to the promotion and documentation of Canadian culture.

“The artist brings something into the world that didn’t exist before, and he does it without destroying something else. A kind of refutation on the conservation of matter.” – John Updike.

You know what’s particularly wonderful about this country of ours? Treasures, treasures everywhere. No matter how humble or unlikely the surroundings.

Take Beardmore, Ontario. Towns don’t come much more humble than Beardmore, with it’s population of a few hundred souls nestled in the bosom of northwestern Ontario wilderness about ninety miles due north of lake Superiors arched eyebrow.

It’s a small town, boasting a couple of gas stations, a general store, a motel or two. Hard to differentiate from any of several hundred other small Canadian towns. You could drive right down the main street, past the grocery store and the barber shop and be back out on the highway before you knew it. Thousands do, every year.

Ah, but they miss the treasure that way. It’s the barber shop on Main Street. That’s where Ewald Rentz lives.

Who’s Ewald Rentz? Well, first off, it’s “Ed” to his friends. He was born in North Dakota, drifted around a bit through Manitoba, but made his way eventually to Beardmore, where he fell in ove with the land and stayed.

And since all that happened back in 1939, folks take it for granted that Ed’s there for keeps.

In his 86 years Ed’s done most of the things a Northerner does. He’s been a miner, lumberjack, prospector, cook, and as the candy-stripped pole outside his place attests, a barber.

Oh yes, and one other thing. Artist. Ed’s an artist. World renowned as a matter of fact.

There are collectors in England who salivate for his work. Curators from the U.S., Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver make periodic pilgrimages to the barber shop to see if he’s got anything new they can buy. His work is on display in museums across the country including the National Museum of man in Ottawa.

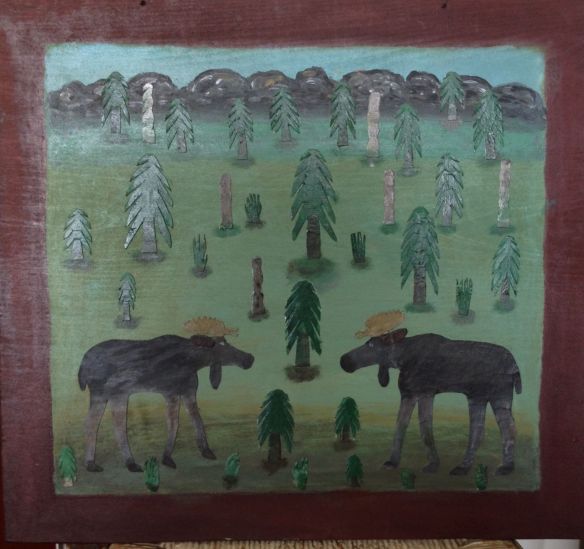

Ed Rentz is a national treasure. And the barber in Beardmore. Ed’s what you call a folk artist. He doesn’t do abstract impressionist canvasses or mobiles a la Henry Moore. Balsam, birch and poplar are his media. His inspiration comes from the bush he’s wandered through for most of his life.

Ed can pick up a chunk of knotted forest debris that you and I would reject as firewood, turn it over in his own gnarled hands, take it back to his workshop and with the help of a knife and chisels, and judiciously applied dollops of house paint, transforms it into the most exquisite and unexpected bit of art – a ballerina perhaps. Or a bear cub. Or a Mountie. Or a great spotted fantasy pterodactyl in full flight, with a man on its back hanging on for dear life.

Ed’s tiny barber shop on the main street of Beardmore is crammed full of his works of wonder. Elves, moose, mermaids, wolves, Prime Ministers.

If you are good, and he’s not too busy, Ed might fetch his step-dance dolls. All meticulously hand carved, out of their special cloth bags, set them on the floor, haul out his mandolin, and make them dance for you.

But have a care. Just because he is a world-renowned artist and an unusually fine chap of 86 winters, doesn’t mean that Ed’s not a working man too. My no. If it’s a Saturday, you may have to talk to him between haircuts. Ed still knows how to give a haircut.

He still knows how to handle knotty customers too – be they balsam or bushworker.

“One time” says Ed, looking at your correspondent thoughtfully, “a nearly bald guy comes in here. I cut his hair. He gets out of the chair and says “wait a minute”. You charged me a buck when I only got a little bit of hair?”

“I told that guy” continues Ed, “I didn’t charge you a buck, I charged you twenty-five cents to cut your hair.

“And eighty cents to look for them.”

Arthur Black

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996.

In retrospect, “no slouch when it comes to art” sounds a bit flippant, when I was meaning to suggest that “no slouch” is an understatement. I had and have great respect and admiration for her taste and instincts, and her contributions to the world of folk art. She was also very nice to me when I was a stranger in the midst of the dealers at the Outsider Art Fair in 1996. Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

Phyllis was interested in the fact that Billy had created his own “wooden” version of Stonehenge in his back forty, and that he occupied it with many Irish leprechauns, and zodiac figures he had created in cement. She imagined having all the work in her gallery, in a type of recreation of Billie’s world. We excitedly talked on about it a bit more, and we agreed that I would look into it when I got home in terms of interest on Billie’s part, and the logistics of getting all that cement to New York.

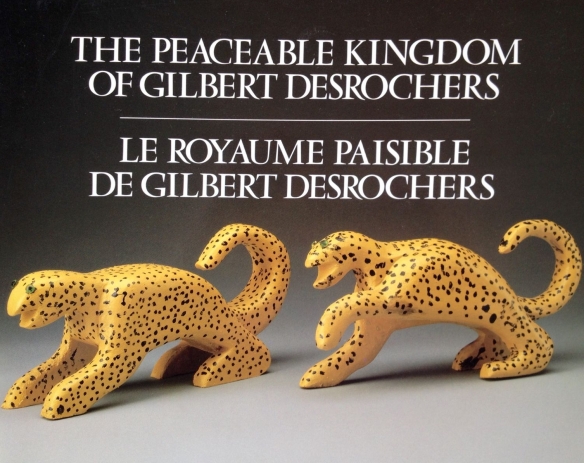

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

Gilbert Desrochers was born on May 2, 1926, in Tiny Township. The fifth child in a family of six boys and one girl. His father Thomas owned a farm on the eighteenth concession, overlooking the bluffs of Thunder Bay Beach. He only attended school for two years when his mother died, and he went to work with his father and brothers on the family farm. “I wasn’t much good in school” he recalled. “I didn’t learn much. I went to school only to smoke. And I slept. I was always so tired that I fell asleep. I had no notion about school. I had only work in my head. I figured that work was easier than school.” Our father couldn’t read or write either and said “it’s just as well that you are like me. Come work with me in the woods.” “My father had two hundred sheep, and we took care of them. Also nine cows, three horses, chickens and pigs. In the winter we would cut wood all the time. We didn’t have a power saw so me and Joseph would cut wood all winter. It was a lot of work with cross-cut saws and Swede saws.

I love it when good things fall out of the blue, right into your lap. It had been a long time since the cosmos had flipped me a lucky card, and I remember thinking about a month ago that perhaps things were quiet because I had been out of the circle for so long (my last show being Bowmanville in 2014) that collectors had basically forgotten about me. It seemed a reasonable assumption, even after 30 years in the business, because it can be a case of what have you done for me lately. But then two things happened. First, I had a call from a Montreal folk art collector I have known for years, but had not heard from for at least ten. He explained that his wife had died recently and it had come time to downsize and disperse the collection. He has some great things so I am looking forward to starting this process. Then the following day I got a call from a lovely woman from Thunder Bay named Alyss Rentz. She was married to Gary Rentz who was Ewald Rentz’ nephew. I am a huge Rentz fan, and it had been a long time since anyone from the family had contacted me. Alyss explained that her husband had died and she too was downsizing; and she has five pieces by Ewald that she would like to sell. As it happened she was coming to Hamilton the following week to visit relatives and she could bring the pieces with her. She described the pieces and after seeing hundreds of Rentz’s over the years I knew from her description that I was interested. She told me she would call when she arrived in Hamilton. Great! I was immediately looking forward to it.

I love it when good things fall out of the blue, right into your lap. It had been a long time since the cosmos had flipped me a lucky card, and I remember thinking about a month ago that perhaps things were quiet because I had been out of the circle for so long (my last show being Bowmanville in 2014) that collectors had basically forgotten about me. It seemed a reasonable assumption, even after 30 years in the business, because it can be a case of what have you done for me lately. But then two things happened. First, I had a call from a Montreal folk art collector I have known for years, but had not heard from for at least ten. He explained that his wife had died recently and it had come time to downsize and disperse the collection. He has some great things so I am looking forward to starting this process. Then the following day I got a call from a lovely woman from Thunder Bay named Alyss Rentz. She was married to Gary Rentz who was Ewald Rentz’ nephew. I am a huge Rentz fan, and it had been a long time since anyone from the family had contacted me. Alyss explained that her husband had died and she too was downsizing; and she has five pieces by Ewald that she would like to sell. As it happened she was coming to Hamilton the following week to visit relatives and she could bring the pieces with her. She described the pieces and after seeing hundreds of Rentz’s over the years I knew from her description that I was interested. She told me she would call when she arrived in Hamilton. Great! I was immediately looking forward to it.

Gnarled Branches, Knots, made into Objects of Art, by Gerry Poling

Gnarled Branches, Knots, made into Objects of Art, by Gerry Poling